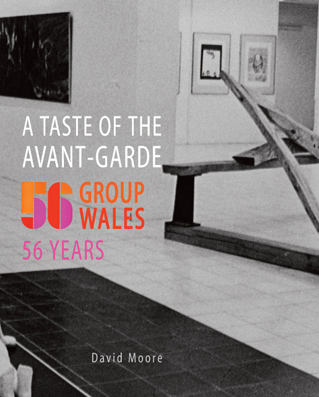

I’d just seen the film On the Road when I went to the Cardiff launch of a book about a group of artists in Wales, A Taste of the Avant-Garde; 56 Group Wales, 56 Years. The room was full of ‘older’ people who had been arty beatniks in the fifties and sixties, like my much admired cousin Dave (who was not only a painter but played the sax, and is still cool of course.) These people were (mainly) still elegant and hip-looking: they had the ever-youthful freshness and bold style of those who had witnessed the dawn of the New Age, an age of self-expression, sexual freedom and spiritual adventure. ‘Oh the parties…’ sighed one woman I met, and I recalled the ecstatic frenzy of the jazz club scene in On the Road. Where would you find that vibe nowadays?

I’d just seen the film On the Road when I went to the Cardiff launch of a book about a group of artists in Wales, A Taste of the Avant-Garde; 56 Group Wales, 56 Years. The room was full of ‘older’ people who had been arty beatniks in the fifties and sixties, like my much admired cousin Dave (who was not only a painter but played the sax, and is still cool of course.) These people were (mainly) still elegant and hip-looking: they had the ever-youthful freshness and bold style of those who had witnessed the dawn of the New Age, an age of self-expression, sexual freedom and spiritual adventure. ‘Oh the parties…’ sighed one woman I met, and I recalled the ecstatic frenzy of the jazz club scene in On the Road. Where would you find that vibe nowadays?

The group was founded in 1956 by a three abstract artists who wanted the power to show and promote their own work – David Tinker, Eric Malthouse and Michael Edmonds. Before long their numbers had swelled and they were deservedly successful, touring their work round the UK and Europe. You had to be invited to join. As time passed they even allowed a few women in (though never more than 25%) including feminist artists like Erica Daborn and Sue Williams (powerful stuff). Gradually they became part of the art establishment, were resented and reviled by some outside their orbit. They still exist today, though now all sorts of art is represented, not just cutting-edge abstraction.

The earlier pictures in the book are evocative of a world recovering from WW2 when it seemed everything was being discovered for the first time – jazz, sex, drugs, etc – but also an innocent world, a world where sports jackets were still worn, smoking was good for you, and women were usually decoratively secretarial or wifely. Abstract art, like jazz, was a badge of this world. If you didn’t like it, you couldn’t enter. The Welshness was an added touch of cool – in one black and white photo from the seventies, Sally Hudson stands in front of her husband, Tom’s paintings featuring the Welsh map, clad in a long dress, with sleeves and hems bordered in a repeated pattern of the same map.

I am not myself part of the art world and was only at this event because the people who created this book are friends – the scholar and collector, David Moore, and his partner, Sue Hiley Harris, a sculptor-weaver whose extraordinary textile version of her own family tree has been widely exhibited (including a brief, partial glimpse in my chapel.) These two are part of a genial group of artists who animate the small world of Brecon, with their un-self-regarding enthusiasm for art and sociability. At the weekend Sue and David opened their Georgian house overlooking the canal for an exhibition of work from the 56 group Wales. My favourites were the vivid, animalistic canvases of Will Roberts and the dynamic glass sculptures of current member, Antonia Spowers – plus Sue’s own work (though she is not in the group), especially the ghostly veil called Hidden Wave in her attic studio.

To find out more about this fascinating book and other artistic activities in this quiet-yet-buzzing part of mid-Wales, visit the Crooked Window website.

And if you like abstract art, take a look at my talented brother’s website.